Author

Abstract

Scarcity of water and depletion and disappearance of water-bodies are some of the impacts of drought on the water supply. This article explores the slow onset of climate change events and water supply nexus: assessing the impacts in northeast Nigeria. It was found that drought and desertification are some of the slow onsets of climate change events currently plaguing northeast Nigeria. Also, the geological settings of the region coupled with the semi-arid region make northeast Nigeria expose to the risk of low rainfall, which is approximately 600 mm per annum and high evapotranspiration of over 2000 mm per annum, and accessibility to potable drinking water insufficient and unsatisfactory quantity and quality. Drought impacts on water resources reduced annual average rainfall and its run-off influences increase desertification in Nigeria. The Adaptation to adopt is to raise awareness to implement water conservation measures and educate the public on better water use practices, and maintain water facilities by a scheme that allows the users to build back better. The mitigation to embrace is drought forecasting and managing River Basin Development Authorities to promote sustainable utilization of water resources in the dry land. The article recommended a preparedness plan to reduce the drought impacts on water resources.

Keywords: drought, water supply, internally displaced persons (IDP) camps

Introduction

Water is life and good drinking water is keep one from contracting water-related diseases like diarrhea, cholera, and so on. Geographically, access to water is uneven across regions due to many factors. Drought, land degradation, and increasing temperatures have been linked to water scarcity triggered by climate change particularly. The rapid rise and spread of the conflict in northeast Nigeria caused by the Boko-haram have led to thousands of displacement and increased the number of internally displaced persons across the three most conflict states (Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe.) Access to clean water is a major problem in many African countries. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2007 reports shows that one-third of all people in Africa live in drought-prone regions. One-quarter (about 200 million people) currently experience significant water stress (Osonwa, 2020). Safe access to potable drinking water in sufficient and satisfactory quantity and quality has been a challenge in the northeast. This is largely due to being a semi-arid region and climate change.

Analysis of Water Sources and Supplies at internally displaced person (IDP) camps

Generally, water is obtained from two sources, surface water, and groundwater source. Surface and groundwater are used for a variety of purposes. For example, water is used for drinking, cooking, and basic hygiene. It is also used for recreational, agricultural, as well as industrial activities. According to Ground Water Foundation (n.d), groundwater is the water found underground in the cracks and spaces in soil, sand, and rock. It is stored in and moves slowly through geologic formations of soil, sand, and rocks called aquifers. In Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe, hand pumps, protected well, and unprotected wells are the main water supply system in the IDP camps.

Surface water sources are water sources from the surface of the earth. They are the water that collects on the ground or in a stream, river, lake, reservoir, or ocean. Surface water is constantly replenished through precipitation and lost through evaporation and seepage into groundwater supplies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). In IDP camps in Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe, groundwater is the main water source. However, surface water is an alternative water source for some IDPs. According to Save the Children and Mercy Corps, in Biu, Bayo, Hawul, and Kwaya Kusar Local Government Area (LGAs), water is mainly available from streams and wells (ACAPS, 2016).

Furthermore, rainwater is a source of drinking water in the tropic, particularly in northeast Nigeria. Importantly, it is a free source and can be collected in a considerable quantity from roof catchments and other pavement areas which can be used for various purposes (e.g., garden watering, toilet flushing, laundry, cooling and heating, hygienic use, and drinking (Rahman, Rahman, Haque, & Rahman, 2019). Rainwater source is the only easy access water source for IDPs. However, rainwater is seasonal. Besides, the rainy season in northern Nigeria is between May to November according to Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NIMET). As a result, rainwater harvesting facilities are employed within this period and people stored water using water storage. Rainwater harvesting was found to be technically feasible coupled with a corresponding water reservoir as a way to reduce the effects of the five monthly dry spell experienced in the northeast region (Ibrahim, 2017).

The geography of northeast Nigeria makes water source varies with the combination of surface, ground, and rainwater. Refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced persons, and returnees should have access to adequate drinking water irrespective of where they are according to the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (ACAPS, 2016). Access to water, however, remains problematic in the region in terms of availability, access, and quality, although these issues vary widely across geographic space. The provision of sufficient water points and sanitation facilities is a priority need in locations where an influx of IDPs has led to overcrowding (ACAPS, 2016). Payment for water from water vendors and access to public water sources and suitable water containers are all important challenges. In some areas, the main water sources are water vendors and unprotected sources. In Flour Mills area of Maiduguri where informal settlements are mixed within host communities, for instance, 16 percent of the population were highly dependent on water vendors (ACAPS, 2016).

In Adamawa state access to water is an issue for IDPs, particularly those residing in informal settlements or with host communities where water points are broken. There are also significant issues around vector control and drainage systems, in camps, host communities, and informal settlements (IRC, 2016). Open defecation in IDP camps is also a concern: an outbreak of diarrhea in one of the camps in Yola was attributed to contaminated water (OCHA, 2016). In Yobe State the main water sources for IDPs and host communities are boreholes with motorized or solar-powered pumps and water trucking. It is believed that more than 60 percent of IDPs in host communities having insufficient containers for water collection and storage (OCHA, 2016).

Slow on-set of Climate Change Events and Water Supply

The slow onset of climate change events are the weather and climate-related hazards that undergo a slow process before becoming a disaster. For example, desertification/drought, increasing temperature, sea-level rise, ocean acidification, land and forest degradation, and glacier melting. The article focuses on drought and desertification being the slow onset climate change hazards that are peculiar and severe in northeast Nigeria.

Drought, Desertification, and Water Supply Nexus

Drought can be meteorological, agricultural, or hydrological drought. Meteorological drought refers to a precipitation deficit over a period of time. Also, agricultural drought occurs when soil moisture is insufficient to support crops, pastures, and rangeland species and hydrological drought occurs when below-average water levels in lakes, reservoirs, rivers, streams, and groundwater, impact non-agricultural activities such as tourism, other forms of recreation, urban water consumption, energy production, and ecosystem conservation.

According to United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification UNCCD (1997), desertification is land degradation in arid, semi-arid, and humid areas resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities. Desertification, land degradation, and drought have a negative impact on the availability, quantity, and quality of water resources that result in water scarcity (UNCCD, n.d.).

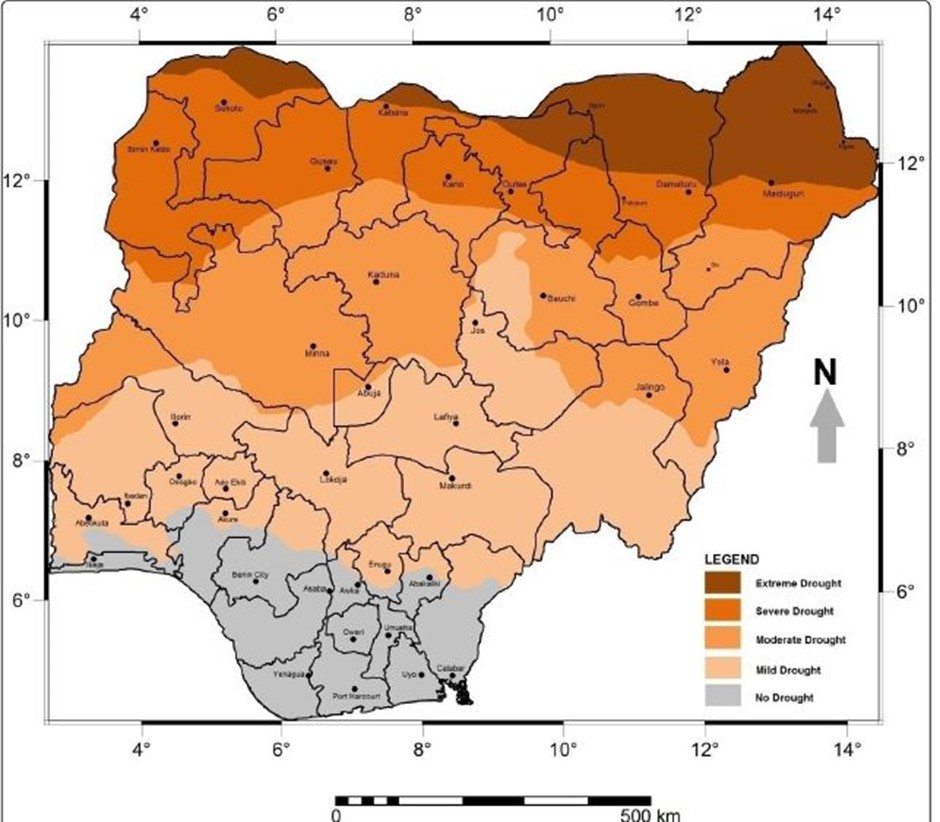

The menace of drought and desertification is one of the ecological disasters currently plaguing Nigeria. Droughts occur throughout the length and breadth of the country. However, they are more frequent and much more severe in the Sudano-Sahelian States of Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara, Katsina, Kano, Jigawa, Yobe, Gombe, and Borno (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2018). For example, in Yobe State, the drying up of rivers, ponds, and other water bodies resulted in increased aridity of the area with accompanying hard socio-economic conditions on the inhabitants of the affected communities.

Figure: Nigeria Map Showing Drought Severity

Source: Federal Republic of Nigeria (2018)

The underlying causes of most droughts in Nigeria can be related to climate change and changing weather patterns manifested through the excessive build-up of heat on the earth’s surface, meteorological changes which result in a reduction of rainfall, and reduced cloud (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2018). The resultant effects of drought are exacerbated by human activities such as deforestation, bush burning, overgrazing, and poor cropping methods, which reduce water retention of the soil, and improper soil conservation techniques, which lead to soil degradation.

However, the implication of this to the water supply is that decline the amount of surface and groundwater. Increasing occurrences of water scarcity, whether natural or human-induced, serve to trigger and exacerbate the effects of desertification through direct long-term impacts on land and soil quality, soil structure, organic matter content, and ultimately on soil moisture levels. The direct physical effects of land degradation include the drying up of freshwater resources, an increased frequency of drought (UNCCD, n.d; Mercy Corps, 2017).

Drought Impacts on Water Access

Geographically, Borno, Adamawa, Yobe lie in the semi-arid region of Nigeria making the states expose to the risk of low rainfall, which is approximately 600 mm per annum and high evapotranspiration of over 2000 mm per annum. The mean annual rainfall of the area is put at 450mm (Sawa & Adebayo 2015). A rainfall amount in the range of 300 – 700mm is anticipated over the North, 1100 – 1500mm over the Central states, and about 3000mm in the coastline (NIMET, 2021). The geological settings of Borno, Adamawa, Yobe coupled with inadequate rainfall make the accessibility of the state to potable drinking water insufficient and unsatisfactory quantity and quality. The long-existing water scarcity history of Pulka, Gwoza Local Government Area of Borno State, resulting from the geological setting, water supply across the camps is fulfilled through water trucking (OCHA, 2020, May). In Maiduguri, Borno, the water table is low, requiring new boreholes to be around 100m deep ((ACAPS, 2016). Drought conditions in parts of Northern Nigeria have also resulted in less drinking water (Sayne, 2011). Similarly, drought is highly linked to the drop in the water levels of rivers and streams and the lowering of the water table, most of the rivers and streams in drought-prone areas flow into Lake Chad (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2018). Reports have also shown that drought exacerbated the shrinking of the Lake (Dioha & Emodi, 2018; 29; Elisha et al., 2017).

Besides physical scarcity, contamination of water sources can occur during drought conditions. In Sabon Kaswa and Azere, in Kwaya Kusar LGA of Borno, the water table is high and therefore easily contaminated according to Save the Children and Mercy Corps (ACAPS, 2016). Water reservoirs may experience increased pollutant levels and lower levels of oxygen, contributing to higher concentrations of illness-causing bacteria and protozoa, as well as toxic blue-green algae blooms, reduced flow levels in rivers and aquifers can allow saltwater to move inland and also contaminate the water supply. Most water treatment plants are not equipped to remove salts, which can cause problems not only for potable water but also for industrial use (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2018). Drought impacts on water resources reduced annual average rainfall and its run-off would increase desertification in Nigeria.

Table 1: Historical Impacts of Drought in Nigeria

Period | Name | Areas Affected | Impacts |

1903/1905 | – | Most of Northern Nigeria | • Described as mild. • Poorly documented but believed to have been caused by the early cessation of the rains leading to poor harvests of grain crops and famines. |

1923/1924 | Mai Buhu | Katsina, Kano, Borno | Late-onset of rainfall and poor distribution during the rainy season led to famine. |

1942/1944 | Yar’Gusau | Sokoto, Katsina, Kano. | Inadequate rain aggravated by World War 11 economic recession. |

1954/1956 | Yan Dikko | Sokoto, Katsina, Kano, and Borno, regions | Wilting of crops and drying up of grasses |

1972/1973 | – | Most of Nigeria but particularly very severe in the northern states | • Farmers recorded 10% of the expected yield. • 105,876 Cattle, 168,918 Sheep and Goats, 38,300 Donkeys, 4,422 died • Ground water level dropped everywhere in the Sudano-Sahelian part of the country. • Prices of foodstuff rose by 400% •Severe hunger and famine all over the Sudano-Sahelian zone |

Federal Republic of Nigeria (2018)

Water Supply: Adaptation and mitigation to the risk of slow on-set of Climate Change Events

Adaptation

- Raise awareness to implement water conservation measures. For example, rain harvesting. Educate the public on better water use practices. For example, wastewater recycles practices. Avoid pollution caused by anthropogenic activities to ground and surface water

- Maintain water facilities by a scheme that allows the users to build back better.

Mitigation

- Provision of irrigation and water pumps to the affected population exposed to drought impact

- The effective policy response in managing River Basin Development Authorities to promote sustainable utilization of water resources in the dry land

- Drought forecasting should be promoted and effective. This will help to formulate drought and desertification policies and a national drought preparedness plan.

Recommendations

There should be adequate and regular capacity building for drought monitoring, assessment, and forecasting particularly for key agencies or institutions like NIMET. A preparedness plan is essential to reduce the drought impacts on water resources.

Further, focuses more on risk mitigation of drought impacts on water resources instead of putting huge efforts on emergency and relief measures. Risk mitigation such as drought monitoring and early warning system, drought impact and vulnerability assessment, and planned actions on drought management will be a help to be proactive to the risk of drought in northeast Nigeria. Further study on the impact of drought on water access and sustainable water supply at IDP camps is needed and exploring sustainable water supply water scarcity.

Conclusion

The slow onset of climate change events such as drought and desertification has an impact on water resources. The northeast region is in the semi-arid climatic zone and exposing largely to the risk of drought and desertification than the other part of the country. This study explores drought, desertification, and water supply nexus as well as the impact on water resources. Stakeholders being proactive to slow onset of climate impacts on water supply by making policies and action plan that reduce the drought impacts on water resources will help build sustainable water supply in northeast Nigeria.

References

Abubakar, L.U., & Yamuda, M.A (2013). Recurrence of drought in Nigeria. Cause, Effects and Mitigation. International Journal of Agriculture and Food Science Technology. ISSN 2249-3050, Vol.4 No.3. pp.169-180.

ACAPS. (2016). Crisis Profile-North east, July 2016. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/assessments/160712_acaps_crisis_profile_northeast_nigeria_b.pdf

Adamu, J. I. (2020). Nigerian Meterological Agency. https://fscluster.org/sites/default/files/documents/2020_srp_fss_abuja.pdf

Azare, I. M., Abdullahi M.S., Adebayo, A.A., Dantata, I.J.,& Duala, T. (2020). Deforestation, Desert Encroachment, Climate Change and Agricultural Production in the Sudano-Sahelian Region of Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. Vol. 24 (1) 127-132 January. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jasem

Brouwer, C., Hoevenaars, J.P.M., van Bosch, B.E.,Hatcho, N., & Heibloem, M. (1992). Irrigation Water Management: Training Manual No. 6 – Scheme Irrigation Water Needs and Supply: 2. Water Sources And Water Availability. Food and Agricultural Association. http://www.fao.org/3/U5835E/u5835e03.htm

Daily Trust. (2019, April 22). Heatwave Hits Borno, Kano, Adamawa, Katsina, Others. https://dailytrust.com/heatwave-hits-borno-kano-adamawa-katsina-others

Dioha, M. O. and Emodi, N. V. (2018). Energy-climate dilemma in Nigeria: Options for the future. IAEE Energy Forum. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=108&ved=2ahUKEwihv4iA2-7kAhVoc98KHWNKDtw4MhAWMDl6BAgQEAI&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.iaee.org%2Fen%2Fpublications%2Fnewsletterdl.aspx%3Fid%3D465&usg=AOvVaw3qHlxFJnRFCXox9HBg4d-I

Elisha, I. et al. (2017). Evidence of climate change and adaptation strategies among grain farmers in Sokoto State, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT), 11(3), 1-7. http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jestft/papers/vol11-issue%203/Version-2/A1103020107.pdf

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2018). National Drought Plan. Federal Ministry of Environment. https://knowledge.unccd.int/sites/default/files/country_profile_documents/1%2520FINAL_NDP_Nigeria.pdf

Groundwater Foundation. (n.d.). HAT IS GROUNDWATER? https://www.groundwater.org/get-informed/basics/groundwater.html#:~:text=Groundwater%20is%20the%20water%20found,sand%20and%20rocks%20called%20aquifers.

Haider, H. (2019). Climate change in Nigeria: Impacts and responses. K4D Helpdesk Report 675. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/14761/675_Climate_Change_in_Nigeria.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ibrahim, U. A. (2017). Appraisal Of Rainwater Harvesting Potential In Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323013764_APPRAISAL_OF_RAINWATER_HARVESTING_POTENTIAL_IN_MAIDUGURI_BORNO_STATE_NIGERIA

IRC, (2016) Annual Report-Humanitarian Response north East Nigeria, January to December 2016

King, M. D. (2019). Water Stress: A Triple Threat in Nigeria. Pacific Council On International Policy. https://www.pacificcouncil.org/newsroom/water-stress-triple-threat-nigeria

Mercy Corps. (2017). LAKE CHAD BASIN Mercy Corps Position Paper. https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Lake-Chad-Basin-Mercy-Corps-Resilience-Position-Paper-February2017.pdf

NIMET. (2021). 2021 Seasonal Climate Prediction (SCP). https://www.nimet.gov.ng/download/seasonal-climate-prediction-2021/

OCHA, (2016). Annual Report: a year of challenges and unprecedented needs

OCHA. (2020, May). Fact Sheet: Pulka, Gwoza Local Government Area of Borno State, North-east Nigeria. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/ocha_nga_pulka_factsheet_01052020.pdf

OCHA. (2021, Feb. 4). Nigeria Situation Report. https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/nigeria/

Osonwa, J. (2020, July 21). Call for inputs: Internal displacement in the context of the slow-onset adverse effects of climate change. For the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of internally displaced persons. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/IDPs/Other/john-osonwa-idp-climate.docx

Rahman, M. M., Rahman, M. A., Haque, M. D., & Rahman, A. (2019). Chapter 8 – Sustainable Water Use in Construction. Sustainable Construction Technologies. Life-Cycle Assessment. Pages 211-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811749-1.00006-7

REACH. (2020). Informing Adamawa and Borno – Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH). https://www.impact-repository.org/document/reach/84eae571/REACH_NGA_Factsheet_Borno_STM_H2R_WASH-1.pdf

Sawa, B. A., & Adebayo, A. A. (2015). Derived Rainfall Effectiveness Indices as Evidence of Climate Change in Northern Nigeria and Implications for Food Security, Journal of Agriculture and Biodiversity Research, 4(2) 26-36.

Sayne, A. (2011). Climate change adaptation and conflict in Nigeria. Washington, DC: USIP. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Climate_Change_Nigeria.pdf

Selim, L. (2018). 4 things you need to know about water and famine. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/stories/4-things-you-need-know-about-water-and-famine

UNCCD (1997). United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. http://www.unccd.int

UNCCD. (n.d.). Water scarcity and desertification. UNCCD thematic fact sheet series No. 2. https://catalogue.unccd.int/24_loose_leaf_Desertification_water.pdf

UNDP. (2018). National Human Development Report 2018 – Achieving Human Development in North East Nigeria. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr_2018_nigeria_finalfinalx3.pdf

WolrdData.info. (n.d.). Climate for Borno (Nigeria). https://www.worlddata.info/africa/nigeria/climate-borno.php